Login

iFlicks on Twitter

| Dickens at the BFI: Eyebrows, ghosts and silent shorts |  |

|

| Written by Ivan Radford |

| Friday, 23 March 2012 10:17 |

If there's ever been proof of Charles Dickens' long-lasting influence upon film, the BFI's series of pre-1914 short films is it. Dating all the way back to 1901, cinema has been forever besotted by Dickens' work, from the author's grand sweeps across society to his small indoor scenes of poverty-stricken people keeping warm by expensive fires. Oh yes, there've been a lot of Dickens movies over the years. It's a sign in itself that tonight's set of screenings is the second anthology of silent shorts put together by the BFI. Add that to the fact that A Christmas Carol appears frequently in both line-ups and you know what you get? Sick and tired of watching A flipping Christmas Carol. Fortunately, you also get fascinated by a compilation of old creations that you wouldn't see at any other point in your life. Chief of which is the newly discovered 1901 movie, The Death of Poor Joe, the oldest surviving Dickens film, which will be screened as part of tonight's event. (You can listen to Michael Eaton's discussion of the film's significance at the premiere here.) It's curious to see how the relationship between literature and film fluctuated, even in the early days of cinema. Constrained to one or two reels, what can a filmmaker inspired by a full-length novel do? One of my favourite adaptations (from the BFI's first programme in January) was 1903's Dotheboys Hall, based upon (a very small fragment) of Nicholas Nickelby. The film, which lasts no more than a few minutes, is set in a classroom, where Wackford Squeers beats a child with a cane. In steps Nicholas Nickleby, wrenches the weapon from Wackford's sinful hands and starts hitting him round the head with it. Immediately, the kids go wild, turning over tables and running around shouting. One of them grabs Wackford's hat and climbs up onto a desk. The others dance around him. Roll credits. It's wonderfully silly and great to see a classic piece of literature distilled down to a single moment. Need to sum up Nicholas Nickleby in 180 seconds? Man prevents corporal punishment. Boy acquires headwear. Done. Others are more indirectly related to Dickens. One film by none other than DW Griffith, Brutality (1912), sees a violent husband treating his wife in a foul manner for 13 minutes. Then, just as the movie draws to a close, she takes him to see Oliver Twist in the theatre: Dickens' work (and its reforming, moral qualities) had permeated culture so much that it had already acquired that elusive film-within-a-film status. The compilations shed some other interesting lights on cinema at the time as well. The Boy and the Convict turns Great Expectations into a feel-good bromance (I Love You, Magwitch), like a period version of Romeo and Juliet in which the lovers live happily ever after. The Thanhouser Company spend most of 1911's The Old Curiosity Shop sticking their logo on their background sets, in the process introducing the world to one of the first corporate-branded trees. Meanwhile, John Bunny - the John Candy of silent movies - was enlisted by the Vitagraph Company (later bought by Warner Bros) to come over to England and star in The Pickwick Papers. This 1913 production is notable not just for its portly star but also for its portrayal of the villainous Mr. Jingle, who seems to have the biggest ears ever known to mankind. The BFI are only showing the first part of Vitagraph's three-episode project, but even from these few (flawed) minutes you get a sense of Bunny's chunky charms, all rolling eyes and toppling gait. He was apparently mobbed by fans when he arrived in the country. One can only imagine what his facial expressions would have been like.

But when it comes to famous men and Dickens, all anyone wants to hear is about is Scrooge. Scrooge, Scrooge, Scrooge. Old Ebenezer's appeared in 94 movies over the last 110 years (almost one movie per year). And, if you believe the Zenith Film Company, Seymour Hicks starred in ALL of them. "As played by Seymour Hicks for over 2000 performances!" boasts the opening titles. Hats off to Zenith Film Company, they certainly knew how to cash in on a theatre sensation. In the Dotheboys Hall of life, Zenith Film Company were the boy dancing on the table clutching his newly-obtained headwear.

(Thanks to CED Magic for these images.)

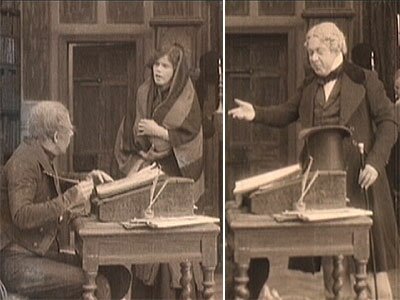

Hicks' Scrooge is a masterclass in hammy acting. From his gibbering mouth and elaborate make-up to his wobbling knees and darting eyes, he makes The Muppet Christmas Carol look like melodrama. He even gets extra scenes not in the book to prove how grumpy and miserly he is, dismissing a poor woman with a baby and snubbing a mayor who looks strangely like Boris Johnson.

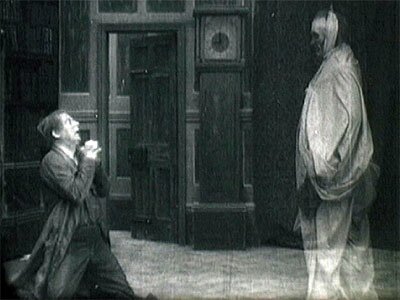

Compare it to the second A Christmas Carol on the BFI's bill (tellingly not titled after its lead character) and the latter is a far subtler piece. But it's interesting to see the difference in effects - not least in the presentation of the ghosts who visit Scrooge. Harold Shaw's 1914 production has Scrooge taken out into the world by the spirits via the magic of double exposure. He is transformed into a faded spectre, wandering the streets of other people's existence before returning back to his bed via a closed door and, still superimposed, lying down on top of himself and sleeping. This is the kind of trickery we expect from an on-screen Scrooge adventure and can even be found in 1901's Scrooge, or Marley's Ghost.

In Leedham Bantock's approach, on the other hand, we stay inside Scrooge's home. The ghosts visit him, faintly appearing behind his fully-formed flesh, while he gesticulates at thin air and begs them for forgiveness. The wonder of the spirits is at work, the film seems to say, but dammit, this is Seymour's show. Is it a lack of money that forces such constraints? Is it an artistic decision to adopt Scrooge's perspective? Is it something stipulated by Seymour Hicks so the world gets a better chance to admire his massive fake eyebrows? That's the one thing you do learn from the BFI's bicentennial season of Dickens adaptations: no matter how old the film, Ebenezer Scrooge's eyebrows can never be too big.

Pre-1914 Dickens Short Films (Programme Two) is on at the BFI tonight at 18:20. Go see it.

Tags:

|

|